In 2017, a statue of Friedrich Engels was transported on a flat-bed truck from eastern Ukraine, a former colony of the Soviet empire, to the heart of the ‘northern powerhouse’ of England - Manchester. As a result, a man recognised as instrumental in shaping 20th-century Marxism is remembered in the commercial nexus of a city, where the first industrial revolution began and capitalism truly took hold.

Born in 1820, Engels was the son of a Prussian-based father who ran a successful textile business. His family were wealthy, however, from an early age Engels found the human costs of this prosperity hard to bear. This soured the relationship he had with his father, who arranged to send Friedrich – at the age of just 22 – to manage a cotton mill he part-owned in Salford, just outside Manchester. At that time, Britain was by far the most advanced industrial economy in the world, a leader in the production of cotton, coal and iron. However, Engels was profoundly impacted by the poverty and misery he saw in Manchester and during his evenings and weekends visited various districts and homes to better understand the social consequences of the industrial revolution. This resulted in the 1845 publication of his book The Condition of the Working Class in England. Notwithstanding becoming a renowned account of the terrible conditions in which workers lived, woven into the content was an economic analysis of capitalism, which Karl Marx and Engels later developed.

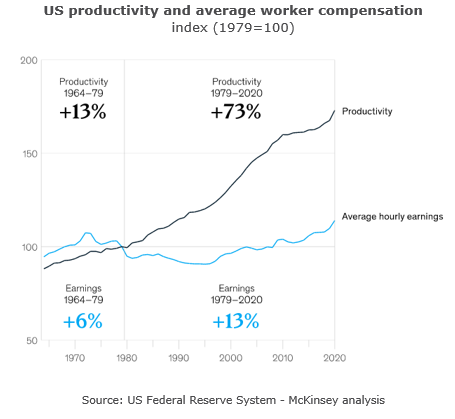

The social perils of unregulated capitalism which reigned at the time are well documented, but understanding the divergence between rising productivity and stagnant wages, during a period of significant technological change, is an important consequence of Engels study. Clearly, it deeply resonates with the period of economic development the world is currently facing on a number of different levels.

The resemblance to the twenty first century is striking

We have entered an age where anyone will be able to produce anything, anywhere – thanks to 3-D printing; where anyone can broadcast their performance anywhere, thanks to YouTube; and can sell anything, anywhere through platforms such as Tmall, Amazon or Shopify. However, this new golden era of opportunity and technological advance is also associated with stagnant wages, insecure employment and striking inequalities. If we return to 1840 and substitute machine learning for the steam engine, Twitter for the Telegraph and fulfilment centres for cotton mills, the resemblance is striking. Moreover, between 1820 and 1840, England experienced vigorous GDP growth, but this was not matched by rising incomes for workers. The chart illustrates a similar period in the US where, between 2000 and 2018 – another period of exceptional technological progress – growth in annual wages amounted to just 0.9% annually.

This period of divergence, during UK economic history, is known as ‘Engels pause’ – based on the observations and research undertaken by young Friedrich at that time. Debate is ongoing as to whether the US and the rest of the developed world are currently undergoing another such period. We are now in the fourth industrial revolution (the advent of Artificial Intelligence and robots), where the impact on society could be more intense in terms of scope, scale and speed, when compared to nineteenth century England. This is something we touched on in our last VFTD, with the challenges it creates to achieving inclusive prosperity. We have entered a period where building social capital will require a sense of purpose and common values among individuals, companies and even countries.

Enter ‘net zero’ and the need for a fair and just transition

Net zero describes achieving a balance between the Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) emitted into the atmosphere, by the global economy, and those removed from it; with unavoidable, residual emissions compensated by using nature-based carbon removal solutions. This intergovernmental goal has been established in response to the climate change crisis, which threatens societies and livelihoods around the world. Remedies to this are inextricably tied to our fiscal, economic and social wellbeing. Expectations have coalesced around climate action, but this societal coalition will not hold if the economic transition required to achieve this is not fair and just. Environmental sustainability cannot be achieved if it comes with a fall in living standards and rising unemployment. Equally, the solutions to the climate problems faced may not be found with sufficient speed without market forces driving efficient capital allocation and driving innovation.

The current momentum associated with addressing climate change will be maintained if the efforts to do so are tangible (help given to improving the energy efficiency of homes and the purchase of EVs), predictable (public policies which encourage private investment) and equitable (support provided to countries, regions and sectors which will undoubtedly face significant adjustments).

So, is the green investment opportunity attractive enough?

The majority of capital owners will require a return on money committed to achieving net zero. Fortunately, it seems clear a set of factors have aligned to create an attractive investment environment. Namely;

- The post-Covid recovery remains unpredictable, with supply chain disruption, a cautious consumer and pressures on employment, all combining to highlight economic recoveries will be determined by investment.

- The lower-for-longer interest rate environment means large-scale public investment is relatively affordable.

- Prospective investment themes are huge and diverse. For example, electrifying surface transport and a large share of building heating, in addition to powering industrial processes, will require at least a doubling in total energy production to meet global demand. Efficient energy consumption will also require smart grid software and high-speed interconnectivity via optical fibre technologies and 5G networks.

- The above will create high-paying jobs and advance competitiveness, particularly for those companies that invest in the intangibles of training and identify the new skills required for the green economy.

- The financial services sector is fast recognising the transition to net zero is the future of finance.

-

Implications for portfolios

The speed at which the world progresses on its journey towards a net zero carbon economy is dependent on: policymakers; the targets and policies they set for reducing emissions; the willingness of companies to adapt; as well as the development and adoption of technologies that can assist in this change.

According to a survey, undertaken by Fidelity International and Longitude International Investor, more than 90% of asset owners and wealth managers – across Europe and Asia-Pacific – say that portfolio decarbonisation is a priority for their institution. To calibrate the potential impact of this, the UN-convened Net-Zero Asset Owners Alliance, formed by over 30 of the world’s largest institutional investors, oversees more than US$5 trillion of assets. With a figure including even more zeros is the $94 trillion represented by Gfanz; namely the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (launched 2021). This number contains no double counting and reflects the signatories of over 450 financial institutions, with around 40% of the world’s assets on their books. Together, they have joined forces behind a common goal: to steer the global economy towards net-zero emissions, by 2050, and deliver the Paris Agreement goals. A period of mission-orientated capitalism is clearly upon us, where the public and private sectors must work together to solve the climate crisis in a way that also maintains and improves living standards globally.

As a consequence of this, the vast majority of private capital will be invested sustainably. There will be years where this approach pays significant dividends for investors and others where it proves more challenging. However, over the long-term, there is no question this is the direction of travel and we must allocate capital to businesses contributing to solutions, rather than those causing the problems. As with all themes, there will be pockets of overvaluation and hype, which need to be actively managed and a focus on valuations remains paramount.

Another key issue for portfolio managers and also for policymakers, this time with a more macro perspective, is the one of greenflation. This occurs when government-directed spending increases demand for materials needed to build a cleaner economy. At the same time, tightening regulation is limiting supply by discouraging investment in significant carbon emitters. The unintended result is rising prices for metals and minerals such as copper, aluminium and lithium that are essential to renewable technologies. To quote Rushi Sharma, Morgan Stanley Investment Management’s chief global strategist;

“The world faces a growing paradox in the campaign to contain climate change. The harder it pushes the transition to a greener economy, the more expensive the campaign becomes, and the less likely it is to achieve the aim of limiting the worst effects of global warming.”

We need to recognise shutting down parts of the old economy too quickly runs the risk of pushing the price of building a cleaner beyond reach. Long-term the shift to a sustainable economy should be neutral to disinflationary, and also drive real growth. In the interim, we all need to adjust to higher prices and higher taxes, meaning central bankers – with the significant power and tools at their disposal – have great responsibility in ensuring a fair and just transition. They need to think carefully about which tools to use and ensure assets that are climate-damaging do not just get shunted around, from the listed sector to the non-listed sector or from banks to shadow lenders.

What would Engels think about all of this? In our view, he would be concerned the forces of capitalism are risking the future for all. However, on a more positive note, perhaps he would hope we are seeing a shift from pure greed, as the driving force of civilisation, to one where capital is a force for good – in other words, mission-orientated capitalism.

Sources;

Value(s) – Climate, credit, covid and how we must focus on what matters; Mark Carney

How the world’s asset owners are confronting the climate challenge; Fidelity International

Please do contact us with any questions.